As soon as I left for Boston and started posting all those pictures of places I was visiting, Ling began dropping big hints about our upcoming opportunity at the end of this year for a holiday to makeup for the three overseas trips in the last 15 months I’ve gone on without her. While most of my planning so far has been for a 10 day stay in Japan, I’ve continued to keep an eye on other locations, including New Zealand, Arizona (a third trip to the US in 2 years!), and Central/Eastern Europe.

Japan’s an interesting choice, especially since Ling wants so much to visit the place. I’m alright with it but not as enthused and I’ll explain why later. But December is also when the country is in winter. A very different experience from visiting the Kansai region in August to September for instance.

In any case, I’ve been wanting to write about my somewhat conflicted feelings about Japan since the middle of last year but been putting it off as I try to keep our blog light-hearted.

Basically, as fascinating as Japanese culture and the country might be to many persons and that some of us go all gah-gah over things that are Japanese, my perspective of the island country and its people is greatly influenced by its history and its actions in the last century. The 1.3 billion Chinese up north certainly have not forgotten, and while I feel little kinship to my parents’ relations still living on Hainan island, I share some of the ambivalence the Chinese have about the Japanese. And specifically, it’s their psyche that I’m thinking about here.

—

My earliest recollections of Japanese history in the last century comes from more than 30 years ago. My dad had a number of pictorial books from our old place in Sembawang Hills Estate, several of which I think are at least half a century old now. I remembered curiously taking out those books to look at as a young boy. One of the books had numerous pictures of the Japanese Imperial Army’s activities in China in the last world war.

Those pictures were not censored. And the photographs of rape, execution, disemboweled body parts and heads held up for display left an indelible impression on my young 7 year old mind back then.

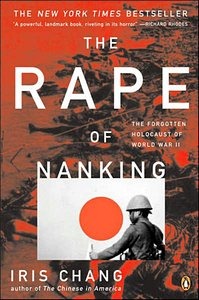

In the subsequent decades, my impression of Japanese brutality got more evolved as I became an avid reader of world history. It wasn’t the graphic pictures anymore, but the text in the historical re-accounts – which admittedly might be biased – and the numerical and statistical representations – which is harder to argue against – of various incidents demonstrating that brutality. That impression got permanently burnt into my consciousness when I read Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking years back – and it’s a book that is best digested in short, separate reading sessions given its seriously depressing and haunting account.

In the subsequent decades, my impression of Japanese brutality got more evolved as I became an avid reader of world history. It wasn’t the graphic pictures anymore, but the text in the historical re-accounts – which admittedly might be biased – and the numerical and statistical representations – which is harder to argue against – of various incidents demonstrating that brutality. That impression got permanently burnt into my consciousness when I read Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking years back – and it’s a book that is best digested in short, separate reading sessions given its seriously depressing and haunting account.

And it’s not just the Nanking incident. When James Doolittle led his small force of American B25s and hit Tokyo in a retaliatory strike after the devastation of Pearl Harbor – and Doolittle did very little actual damage – the Japanese took it out on the Chinese villagers by killing another 250,000 of them. Germ warfare was used.

Or of the Hiroshima sympathizers. The nuclear bomb that Enola Gay dropped on the city caused a huge amount of death and destruction. The Japanese there today continue to emphasize to visitors the extent of suffering they endured, but gloss over the fact that Hiroshima was where their regional army headquarters and a huge depot of military supplies were situated. In comparison, the city of Nagasaki, similarly bombed, seemed to have moved on in sentiment.

I’m not a prude, and I think men are capable of great evil whichever race and nationality. However, there is one theme that all the authors I’ve read agreed on, and it was a theme that struck me first as a young adult: that the Japanese have never properly reconciled themselves to their own actions in the last 70 years of our world’s history. History continues to get whitewashed in their textbooks. Figures that show the extent of their violent actions are disputed by their scholars when they are corroborated everywhere else. Lone individuals – some of whom are formerly serving military officers – who possibly in an exercise of epiphany on their deathbeds try to revisit their country’s actions and seek recounting, but are invariably shouted down by their countrymen in nationalistic fervor.

While there’s the argument that the Japanese actions in South-East Asia were primarily driven by the need for precious natural resources, their actions in North Asia were largely territorial. And in both theaters, they saw themselves racially superior. Everybody else was inferior and less deserving.

—

To be honest; it’s the latter that lingered at the back of my mind when I interacted with the Japanese last December, or when someone around me today gushes about how great their culture and people are.

To be fair, I do find the Japanese very polite, their civilian infrastructures of transportation and communication both efficient and effective (I wouldn’t say the same about their national governance though), and many aspects of their living environment admirable, including care for personal hygiene, respect for authority and the elderly, the naturally beautiful country they live in, and the exquisiteness of their cuisine and dress. I certainly enjoyed my teaching trip to Kumamoto last year and the hospitality of their staff.

But my admiration of Japanese hospitality is also simultaneously tempered by an unsureness that whether beneath that façade lies the potential for yet another explosion where underlining traits that they demonstrated 70 years ago will resurface again, and violently. There has never been the same kind of self-reckoning or actualization that the Germans experienced in post-war Europe.

That said, my bet is that come year end, of the several shortlisted vacation spots, it’ll be Japan that we’ll visit. I have to think of the wife!

well according to some old archives…the dropping of the atomic bomb was actually unnecessary given that the Japanese had agreed in private conferences to surrender. However, they refuse to surrender unconditionally…hoping to retain the dignity of the emperor. The Atomic bomb was still dropped nevertheless because of 2 reasons: to test the bomb on a highly dense and populated area so as to witness its effects and secondly, to show Russia its military prowess.

So in actuality…the Western powers are not entirely clean of innocent blood shed either. As much as they claim that they are fighting a Just war, the purpose behind the dropping of the atomic bomb involves so much more hidden agendas.

Think Howard Zinn will be able to give a clearer commentary on this.

I think the Japanese text books are moving from the path of total denial of the occurence of the Rape of Nanking…to giving an emotionless account of it in the school curriculum. Instead of using words like Invasion…they use words like advancement. etc.

There are however an increasing number of Japanese scholars that are coming to terms with the war crimes of the war. This is such that even within the Japanese academic field, there are fierce and relentless debates to this day. So i guess in this sense, there is a moderate progression from denial to partial acceptance of their war crimes. This is at least true in the academic field even though it is far from true at the official national level.

Hi Xin Wei,

I’ll have to disagree with you on the generally accepted reasons on the dropping of the two atomic bombs. While the two you’ve listed there might had been on a long list of desirable outcomes, I’ve never observed or seen or read anything from mainstream literature to even hint that those two reasons were considered the two ‘key’ reasons.

Coincidentally, and this was pointed out by several other war historians in the last decade, that there was just prior to the turn of the century an interest in revisionist history, especially on the ethics of the allied bombing offensive over Europe and Japan; and their new wave of literature was seeking to recorrect again those perceptions. One book on my shelf that deals specifically with Arthur Harris (The Bomber War, Robin Neillands; hard to read, messy, but I agree in the general about what he was saying) certainly makes a big point of it and criticizes these revisionist looks, as do a couple of others whose books aren’t with me at the moment (they’re in the office).

Either way, I don’t disagree that the allied forces’ hands weren’t clean. But while there was racial bigotry exercised on both sides to dehumanize their opposing sides in wartime, 70 years after the fact, as far as the last world war is concerned I think the Japanese still have a long way to go towards some form of national debate or realization of their actions compared to the western world, which ironically has made possible those alternative viewpoints you’ve offered in your comment.